by Stephanie Folk

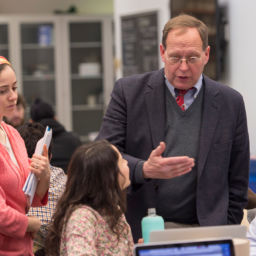

For Kenneth Bridbord, MD’69, getting the lead out of gasoline was the first of many public health successes in a remarkable, half-century career.

Bridbord was drawn to the University of Chicago because of its reputation for rigorous scholarship and research. As a medical student, he also had the opportunity to volunteer in community health projects. And it was those experiences that inspired him to commit his life’s work to global public health.

After earning a master’s degree in public health from Harvard University, Bridbord worked for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). He played an instrumental role in creating regulations limiting the lead content of gasoline. The regulations, which went into effect in 1976, had a dramatic impact.

“In the first four years of implementing the regulation, blood lead levels not only in children, but also in adults, across the United States dropped by 37 percent,” said Bridbord. “That ended up being a much greater impact than I think anyone would have anticipated at the beginning.”

After four years with the EPA, Bridbord spent eight years at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health before moving on to the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

In 1987, he co-chaired the third International Conference on AIDS in Washington, D.C. Discussions during the conference convinced Bridbord that Fogarty could assist in the global AIDS crisis by building sustainable medical research capacity internationally, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

To accomplish this, he developed Fogarty’s pioneering AIDS International Training and Research Program. This program and others that grew out of it have supported training for more than 6,000 health scientists worldwide.

In many regions, particularly in Africa, the results have been transformative, helping to establish and expand local scientific, medical and public health knowledge. Those trained through Fogarty have gone on to train others. They have assumed leadership roles fighting AIDS, responding to Ebola outbreaks and addressing other public health concerns.

Bridbord retired in late 2018 after nearly 35 years at Fogarty, and nearly 50 years with the federal government, but he remains involved with Fogarty in the capacity of senior scientist emeritus. He has also stayed connected to the University of Chicago, attending his fortieth and fiftieth reunions at Pritzker. At the fortieth reunion, he had a memorable conversation with the late Dean Joseph Ceithaml, who was then 98 years old.

“I said how much I appreciated all the support he gave me,” Bridbord said. “He said how proud he was of the things I had managed to accomplish at that time. So that was very special to have a chance to say that to him personally.”

Looking back on his career, he said his time at the University motivated him to contribute to science and research, and his work in government offered an amazing opportunity to make a difference in global public health.

“There’s a huge desire on the part of people to contribute to making the world a better place,” he said. “I would still recommend government as one of the places people can make a huge contribution.”

For his contributions, Bridbord has received multiple honors, including the 1975 Silver Medal from the EPA, the 2007 NIH World AIDS Day Award and the 2009 Distinguished Service Award (now the Distinguished Alumni Award) from the University of Chicago Medical & Biological Sciences Alumni Association.

In retirement, Bridbord is exploring how lead exposure throughout life impacts people as they age and is writing a history of Fogarty’s HIV/AIDS program. For him, public health has been more than a career. It is a lifelong passion for helping others and improving health around the world.

Article originally appeared in the fall 2019 Medicine on the Midway