As students at the Pritzker School of Medicine, Michelle DiVito and Benjamin Kyle Potter, both MD’01, agreed that neither of them would pursue a surgical specialty. “We shook on it,” DiVito said.

DiVito kept the promise. She now practices emergency medicine in the Washington, DC, area. But Potter chose orthopaedic surgery. (It clearly wasn’t a deal breaker; they are now married with three children.)

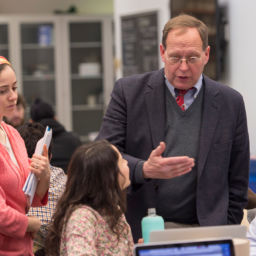

As director of musculoskeletal oncology at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, Potter treats patients with bone and soft tissue sarcomas and cares for active military and veterans injured in combat.

“Walter Reed is one of the major combat casualty care centers in the continental U.S.,” Potter said. After the Boston Marathon bombing in April 2013, the hospital admitted three of the 17 amputees, and Potter consulted on two of the other cases.

Whether caring for patients with severe limb injuries from improvised explosive devices (IEDs) or salvaging a patient’s leg after removing a bone tumor, Potter aims to preserve as much limb function as possible. His specialty requires advanced reconstruction techniques and creativity. For some patients, he harvests bone from other parts of the body to reconstruct the resected bone and save the limb. In other cases, he performs rotationplasty — removing a portion of the leg and rotating the patient’s foot and ankle to act as the knee joint — which preserves some leg function and allows for a better-fitting prosthesis. Potter also conducts research focused on improving quality of life and limb function for individuals who have suffered blast injuries.

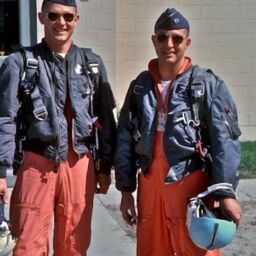

Potter’s training in treating combat wounds was critical when he deployed to Afghanistan for six months in 2011. He served as chief orthopaedic surgeon at Camp Dwyer, then a Marine Corps base in southern Afghanistan. It was a different perspective “seeing people fresh off the battlefield, versus caring for them one to seven days later.” He also treated Afghan women and children who were hurt or who were born with congenital abnormalities. “It wasn’t the type of orthopaedics that I would necessarily do in my day job at home,” he said, “but the patient has no other options.”

As an emergency medicine physician, DiVito also often finds herself in situations requiring quick thinking and action. “Any time I’m in a public place and someone yells, ‘Does anyone know CPR?’ I know I’m on the hook,” she said. One example: DiVito was at a bike shop getting a new tube for the first family bike ride of the spring when she heard a plea for help. A jogger had collapsed just outside the store and was in cardiac arrest, “I whipped into action,” she recalled. DiVito performed CPR until the paramedics arrived with the external defibrillator. Heart function was restored. DiVito called ahead to the hospital, and the man was taken directly to the cardiac cath lab.

“He called me a couple of weeks later to thank me,” she says. “That’s why I love doing what I do.”

“Michelle saves a lot more lives than I do,” Potter said. “I can do a great cancer surgery, but there could be a post-op complication the following week. And we may not know for years whether or not the cancer is cured.”

Potter will do another tour in Afghanistan this summer. He and DiVito, who spent a month in Indonesia doing emergency medicine after the 2004 tsunami, hope to someday work together with an organization such as Doctors Without Borders to provide humanitarian medical care to local populations.

Practicing humanitarian medicine abroad, whether in the military or as a civilian, “expands our scope of practice and teaches us to do more with less,” Potter said. “It helps us think about solving challenging problems in more creative ways.”

Originally published in the Spring 2016 Medicine on the Midway