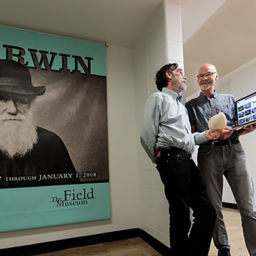

Vineet Arora, MD, AM’03, Herbert T. Abelson Professor of Medicine, became the new Dean for Medical Education on July 1. She sat down recently to talk about her goals for the curriculum and how the global pandemic and social unrest are changing medical education.

You started as Dean for Medical Education 20 years to the day after completing your internal medicine residency at the University of Chicago. At the time, did you ever envision yourself in this role?

At the time, I was just happy to be finishing residency! It was such an achievement. I headed to the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy to get a master’s in public policy and then did my chief resident year, and that’s when I became really interested in medical education. I was working on implementing new residency duty hours at the time. When I became a faculty member in 2004, I got hired as an assistant dean, so I’ve been in the dean’s office ever since. My first role was thinking about curricular innovation, so in a way I’ve come full circle.

Throughout your career you’ve studied areas such as patient handoffs, physician burnout, and creating diverse teams, but teaching and mentoring has remained important to you, as well.

So much about being a scientist is about teaching – and we’re discovering that even more during this pandemic. New science comes out every day, and if you don’t have someone who is able to communicate it and teach it to the public, there’s an opportunity for distortion or an implementation gap.

When I teach, I am also interested in active learning. So much of medical education today relies on memorization, but medicine is often about accessing information and partnering with a team to get a care plan implemented. A lot of my research has been in the clinical environment, and that’s how I approach education. How do we improve learning at the point of care? How do we empower our students to become lifelong learners?

Mentoring has played a big role in your career. Why is it so important?

I’ve studied mentoring, I’ve run mentoring programs, I’ve been mentored, and I’m passionate about mentoring. I’ve seen the rewards, the direct results of good mentoring. In my career, I’m most proud of people I’ve mentored. It’s especially exciting to see the diversity of the people I’ve helped train become faculty members, including women and those who are underrepresented in medicine. Then they become mentors in their own right.

That said, mentoring is a two-way street. I get a lot of emails from students or residents when they are at transition points, asking what they should do next. I tell them that I don’t have the answers, but I can be a sounding board for them. That can be uncomfortable initially. Oftentimes, people can expect you to give them direct orders to carry out, especially in a career like medicine. But my philosophy is to talk about their goals and priorities, and to make sure the investment is on both sides. Mentors can learn a lot of things from mentees.

What have you learned from students or your mentees over the past two decades?

I think many Pritzker alumni would find that the school today is very different than it was many years ago. There’s a huge focus on well-being, advising and work-life balance. I’m certainly not the best person to speak on work-life balance, but students have helped me learn the importance of it. Especially with the pandemic, there have been a lot of questions around separating yourself from work and getting some time to restore yourself. That’s part of a new culture that did not exist before that I do try to model as well.

Speaking of change: You are beginning this role amidst a global pandemic and after a year of social unrest. How has that changed medical education?

Change is never easy. We’re hardwired not to change. But the way you can accelerate change is through urgency, a burning platform, and the past year and a half has given us a burning platform. The pandemic has upended the way education is delivered in this country. It has changed dramatically the way in which we need to empower learners and physicians to lead in our healthcare systems and be advocates for their patients. And the death of so many Black men and women at the hands of state violence has really catapulted the underlying issue of structural racism and inequity into the forefront.

If we cannot use this moment to catalyze and promote change to improve the health equity of our patients and diversify and improve the inclusivity of our learning environments, then that is the epic failure of our time.

How do you hope to promote this kind of change?

First, I’m on a listening tour to understand the needs across our continuum of medical education. One thing our team really wants to do is engage people in building a new vision for our medical school curriculum. We have launched an ideas incubator called Pritzker EVOLVES (Ensuring a Vision of Leading with our Values for Education Students) where faculty, students, alumni and patients can submit ideas. Readers can visit bit.ly/psmevolves to learn more.

You’re looking for ideas, but you likely have a few initiatives that you’re ready to jump in on.

There are a few initiatives that we are focusing on right away. We are looking for more ways to support students who are first generation and low income. We are going to improve the quality of learning space to promote more small group learning interactions, especially as we emerge from the pandemic. We are looking at areas where we can harnass core resources, like simulation and technology, for students, residents, and faculty education.

What about long-term change to the curriculum?

We need to skate where the puck is going. We need to train medical students for the environment of tomorrow. At Pritzker, we’re fortunate to have this strong sense of social justice and health equity, since we’re based on the South Side. The reason many people come here to train is to serve these communities and patients the best way that they can. We are also fortunate to have an excellent health system right here on campus, where we can immerse our learners in a training environment.

That said, we can do a better job integrating students earlier into our health system and into our community to get the training we need. I also want our students to take advantage of our world-class campus and connect with other departments to help them become leaders.

We’re also in an environment where technology is playing an increasingly important role, not just in telemedicine, but in big data and artificial intelligence. The way in which we deliver healthcare now incorporates the doctor, patient and computer — and not just through electronic health records. The computer might actually be advising you on what to do. Students and residents need to know how to interact with that and how to assess if that information is correct.

How does graduate level education fit into all this?

At the resident and fellow level, our goal needs to be to ensure that we are equipping them to transition into practice, no matter what their career path. I’m a huge fan of our Community Champions program, led Anita Blanchard, MD’90, which helps connect residents to the Urban Health Initiative and immerse them in our community. We want to sustain the innovations we are proud of, and also build upon them. And as someone who studies transitions, I also want to help support our learners at their transition points – whether it’s from student to resident, or resident to fellow or faculty. These can be very stressful experiences, and often that is where we see the greatest need and where we have a comparative advantage.

You mention the campus’s location on the South Side, and programs aimed at reflecting that diversity. How does that play into ensuring more doctors are located where they are needed, including in underserved areas of the city?

Our South Side Health Transformation Project (now the South Side Healthy Community Organization), which our hospital is a key leader for, is aimed at addressing health disparities affecting South Side communities through strategic investments. To really improve health outcomes on the South Side, we also need to consider how to address those healthcare workforce needs. We are going to be looking for ways to engage and integrate all learners and faculty so they can understand the need and help fill the gaps.

There is a lot of work ahead, but what excites you most?

A lot of what I want to do is empower people to lead from where they stand. The pandemic has really shown us how this is possible. Our medical students and residents helped with PPE, infection control and getting people vaccinated. Not only did they help society, they also improved their own engagement and satisfaction because they were living up to their scope of practice. Our students and residents do not come to us as blank slates. They have a diversity of experiences, and we want to leverage those experiences to help contribute to healthcare teams and to the overall societal mission of improving health in the community. Leadership does not require a position or a title. It requires a mindset of empowering those experiences to occur.